University School of Milwaukee World Language Teachers Share Their Notes From Visit to the Singapore American School

This past May 2017, my colleagues, Alison Dupee, LS French teacher; Neelie Barthenheier, a MS French teacher and LS and MS World Language Chair; and I returned on fire with inspiration to grow as 21st-century world language educators. We had heard about the Singapore American School’s exemplary world language program from our consultant, Greg Duncan. He described it as one of the best elementary school language programs in the world. When I attended a 2016 ACTFL session last fall conducted by SAS’ Upper School WL Chair, Jean Rueckert, and the MS principal, Lauren Merhbach, I was struck by the similarity of their program and ours. The difference was that they had been working with Greg several years longer than we had, and they had already overcome some of the hurdles we were facing. They had renamed their classes according to proficiency levels, developed an efficient three-year rotating cross-divisional culture plan by language, and most impressively shared video footage showcasing the intermediate skill development of an elementary Chinese and Spanish student. How were they developing such communicative facility so early in their students’ language study? We wanted to know more about their program. What we saw knocked our socks off!

[rule type=”basic”]

English in the classroom?

Novice students– Here and there we heard some English, but very little.

Intermediate – Advanced students- The students and the teachers used Spanish the whole class, even during project planning.

In general, it blew our minds how much Spanish was spoken in the classes we observed. It begged the question: How can we create this culture at our own school?

Do we dare to ……….?

…… ask a student to physically walk out of the classroom and come back in speaking the target language, if the student walks into class speaking English?

……speak the target language with our colleagues in the hallways and in front of students?

……set the tone at the beginning of the year?

……help students learn to do project work in the target language?

……not speak English during class time?

Many USM teachers are doing this!

[rule type=”basic”]

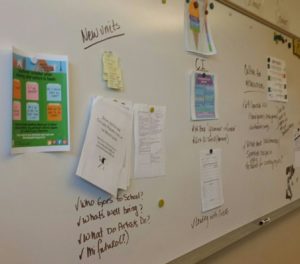

Comfortable Classrooms for Conversation

The elementary classrooms were inviting and comfy. There were no desks and traditional chairs. Instead, in the middle of the room was a group of coffee tables with dry erase countertops with cushioned stools. At the front and the back of the classroom were high top tables and tall stools. On the left of the room was a long whiteboard. The teacher used this as the teacher-input area. On the right of the room were 5 whiteboard stations partitioned off by book shelves. Each of these stations had an identical series of word and grammar walls posted around them. There were also moveable cushions for student to sit on anywhere in the classroom. The furniture was movable, and in fact, for each unit, the teacher used different furniture configurations in order to enhance the current theme or activity. This classroom offered a place for a variety of conversations to be going on at the same time.

In a high school Spanish class, there were beanbag-like cushions on the floor and a couch for students to sit on. When asked about what the students love about Spanish class, the theme of comfy furniture kept coming up. Students strongly felt that furniture helped create a non-threatening environment that encouraged discussion.

Do we dare to change our world language classrooms to promote more relaxed conversational opportunities for our students? Some USM teachers are doing this!

[rule type=”basic”]

Daily Feedback

During pair work, the teacher constantly dropped in and out of various groups in order to listen, ask questions, and generally interact as a group member. This practice allowed for teachers to guide and correct students, answer questions, and gauge student progress. Lyster’s work on feedback was highly recommended for us to explore.

Do we dare to use class time to interact with our students while they are doing group work? Many USM teachers are doing this!

[rule type=”basic”]

Activities that Foster Conversation and are Fun

Many of the classes we observed had stations set up for students to practice communicating. At each station, we observed a different game made with expressions from each unit. While we recognized some of the names of the games, it is important to note that games were adapted to foster LOTS of conversation.

Game stations included:

- Connect Four

- Uno

- Concentration/Memory

- Trampoline/Bosu

- A grid with pockets for cards

- Hop scotch with pockets

- Dots to jump on with vocab pics underneath

- A Bingo-like game where chips were placed on a board of vocab

- Interactive magnets at whiteboard stations

- A play with a curtain at a whiteboard station

Do we dare to be creative about how to promote conversation in our classrooms? We have hired consultant, Katrina Griffin, 2016 ACTFL Teacher of the Year to do a hands-on workshop with us in November in order to grow our bag of tricks for promoting oral proficiency.

[rule type=”basic”]

SAS World Language Culture Curriculum

Novice: The basics, content driven.

Intermediate – Advanced: The Spanish & French teams created a three-year rotating curriculum for the intermediate and advanced classes that is based on the culture of one country. Therefore, every class learns about the same topic and has the same curriculum, but the language goals and tasks are different according to proficiency levels. This plan allows for students to dive deep into cultural topics and language. It is adaptable. It allows for a lot of cross-divisional collaboration. This system makes planning easy, and it is a tremendous time saver. In addition, it allows for the classroom to set the scene both physically and culturally for each theme without the teacher having to quickly take it down before the next group of students arrives for class. For example, in the Picasso unit, the room could be an art studio with easels. Kids at all levels would be set up to paint during the whole unit without the teacher having to rally to get organized for the next class.

Since it is a three-year rotating curriculum, they do not worry about the fact that after the fourth year and beyond that the student will revisit the same country’s topics and content because at that point his or her oral proficiency level is considerably higher. At that point, the student might be accomplishing higher-level tasks with the same content.

To organize the materials, the teachers dump all of the activities into a shared Google folder. Anyone can use and adapt the activities placed in there based on the oral proficiency target.

Do we dare develop a rotating culture curriculum? We are doing it!

[rule type=”basic”]

SAS Readiness Rationale

Based on their research, the teachers at SAS have come to the conclusion that reading comprehension should be introduced when the students have an oral proficiency level of intermediate-high. Before this point, working on reading comprehension interferes with oral proficiency progress.

[rule type=”basic”]

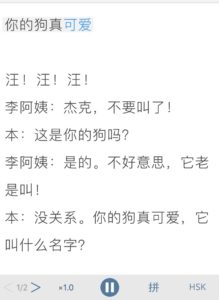

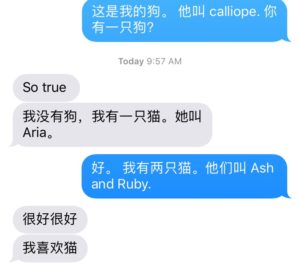

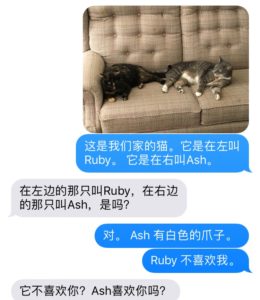

The SAS Reading Program

Starting at the intermediate-high oral proficiency level, students start with level-based readers. They use a program called RAZ (it is the same idea as Reading A to Z). They learn how to read just as our kids learn how to read in the Lower School. Teachers sit down one-on-one with the students to gauge reading proficiency level and assign them a box of books based on the individual reading level. They have trained “helpers” in their classrooms to give students individualized attention,

[rule type=”basic”]

Course Offerings and How Students Progress

Since classes are titled by oral proficiency targets, i.e. Novice (Mid, High) Intermediate (Low, Mid, High), Advanced, students move according to skill level development at their own pace. Students can move up at the semester if they meet the goals for the next oral proficiency level by that time. Since there is no limit to how fast students can progress to the advanced level where elective courses in history and culture are becoming available, many are able to take these elective courses before the end of high school.

Do we dare change the names of our classes? We are in the process of doing this!

[rule type=”basic”]

AP Language Options

Students can take AP language and culture courses in the high school when they have reached an intermediate-high level of oral proficiency; since SAS has elementary language programs in Chinese, French, and Spanish, many students reach that level before their senior year, allowing them a year or even two to take electives in the target language. We observed a Spanish poetry elective class where students were sharing their own poetry while comfortably seated in bean bag chairs on the floor. When we had a chance to ask them about this experience, they raved about the opportunity. Many of them had taken the AP Spanish Language and Culture class the year before and now they were excited to be able to take an elective course.

How awesome is it to think in terms of having students so advanced in oral proficiency that they can explore advanced topics in the language? We hope to do this!

[rule type=”basic”]

Clear ACTFL Proficiency Targets

The ACTFL oral proficiency triangle was posted in every classroom with specific proficiency targets for the different classes.

We have posters in every classroom that stipulate the characteristics of each oral proficiency level.

[rule type=”basic”]

Professional Development at SAS

Teachers work together in teams (PLCs- Professional Learning Communities)coordinating curriculum, analyzing data, and truly seeking the best paths to proficiency for their students. Time is built into the daily schedule for Professional Learning Communities to meet. Each teacher is a valued member of a PLC; in the LS language department, each member had an area of expertise that made them a valued team member.

Do we dare to form Professional Learning Communities? We are doing this!

[rule type=”basic”]

Oral Assessment Feedback

For homework, the teacher asks students to re-watch their own oral assessment video and reflect upon it. The next day, the teacher sits down with a student separately at a table in the same classroom, but apart from the class to discuss reflections. The class works on something else.

During the meeting, the teacher turns on the student oral-assessment video and it plays in the background while they speak about the performance. The teacher starts by asking “Tell me about this last oral assessment.” The student starts speaking about the oral work. If the student starts by focusing on the negative, the teacher redirects the student to the positives. As the student speaks, the teacher asks guiding and follow-up questions only when necessary. Ex: What question words did you use? Did you notice if you were creating language or delivering memorized sentences? What connector words did you use? Were you speaking in full sentences? The students speak at length and in detail in English during their reflection time. The teacher asks the student where he or she hit on the ACTFL oral proficiency scale and then agrees or disagrees with an explanation.

Once the student finishes the reflection, the teacher then coaches the student. The feedback is encouraging and it focuses on functions that will help the student reach up into the next oral proficiency level. The conversation concludes with goals that are set by the student and teacher together. The teacher asks what will be the steps in order to achieve this goal.

Do we dare to take this kind of individual time to help students understand better their own skill level and what it might take to improve it?

[rule type=”basic”]

Singapore! A fading memory that will leave a lasting impression, not only on us but on our students!

Next blog: More details about the way we are changing our program as a result of visiting SAS