It’s important to confess right here at the beginning that I am a firm believer in learning and playing being one and the same—specifically every step along the way from Novice Zero to “survival language” Intermediate Mid-ish. So, the lessons, materials and activities I present and discuss here are firmly rooted in the idea that students need to be doing things (and HAVING FUN) to acquire language in the short term and stick it out long term.

I should preface the rest of this blog post with a quick “About me”. The truly curious can take a peak at my bio, but for now I will briefly say that my name is Matt, I am 23 years old and currently pursuing my M.A. in Second Language Acquisition at the University of Maryland. I have been a Spanish teacher since the age of 16, and a Chinese teacher since the age of 19. As a full time student, I don’t have much time to teach during the school year, but I currently still teach Chinese every summer at a STARTALK program. For those who are not already aware, STARTALK is a federally funded grant program that trains language teachers and provides language learning programs starting at the complete novice level for 11 critical languages in the U.S.

Our STARTALK program’s focus this year was “Family, Food and Festivals on the Silk Road”. Over the three weeks, my topics were Beijing Opera (京剧), the Chinese Tea Ceremony (中国茶道), and the Dragonboat Festival (端午节). Spoiler alert—I am not an expert in ANY of these areas. I am not an opera enthusiast, a tea master, or a festival guru, but I chose these topics for the rich language that could be acquired playing with cultural products and participating in cultural practices. I had to do some research and brush up on a few things, but it was totally worth it! My students ranged in proficiency from complete novice to intermediate mid+ (with a few intermediate highs lurking about), and I worked with each different proficiency group 1 day each week for 70 minutes per week over 3 weeks.

In this series of three posts, I will give you a window into how I tried to teach authentic language in the context of cultural products and practices: Novice Low + Dragonboat Festival, Novice High + Beijing Opera and Intermediate Mid-High + Chinese Tea.

I will conclude each post with a reflection of what worked well and what I would improve if I was going to teach this particular lesson again. Hopefully, that reflection will be some food for thought for you, the reader, as well!

The Dragon Boat Festival – Novice Low

Student Profile:

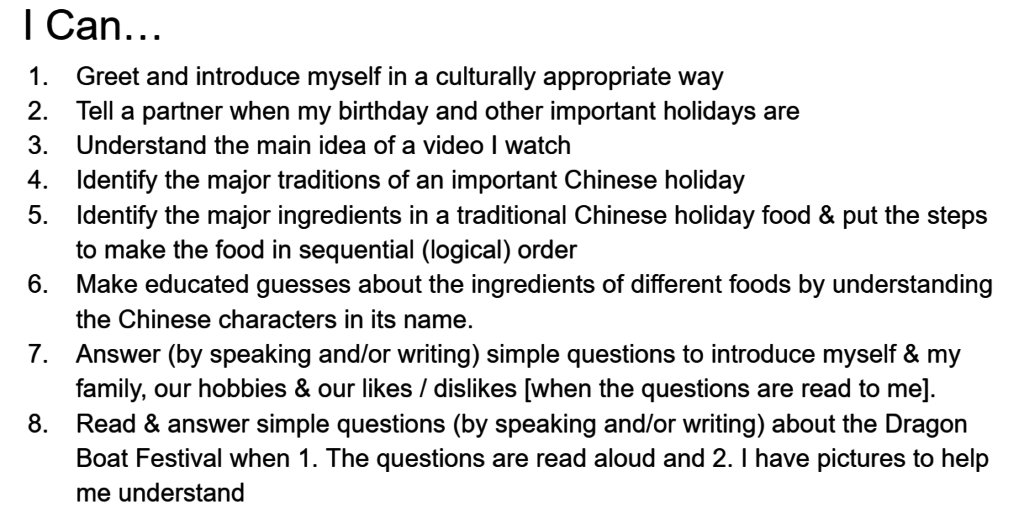

- 18 extremely energetic rising 6-8th-grade complete novices

- Week 3 of the program (Day 14/15)

A note about I Can Statements: I do my I Can Statements by learning episode–in other words, by activity. This way students have a clear idea from the very beginning where our lesson will start, where it will go, and where I expect them to arrive by the end. There are no surprises, and I make sure to leave about 2 minutes at the end of every lesson to go back through the I Can Statements and have them prove that they can, in fact, do them. I randomly select students to read the I Can statements aloud (in English) at the beginning of the lesson, and then I read them myself at the end. As I go through each one, I select a student or two to prove that they can do it—whether this means holding something up, asking a classmate and reporting, or answering one of my questions individually or as a class. This also holds me accountable when I am planning for each learning episode, so that I am sure to include I do, We do and You do activities for each I Can statement.

Task 1 (Interpersonal Speaking)

Task 1 (Interpersonal Speaking)

What is the date for the following holidays? When is your birthday? When is your partner’s birthday? (Differentiation up: When are your family members’ birthdays? When is my birthday? Differentiation down: Is it January? February? etc. until student catches on).

[rule type=”basic”]

Task 2 (Interpretive Listening & “Interpretive Viewing”)

Task 2 (Interpretive Listening & “Interpretive Viewing”)

Authentic Resource Input – Watch the video a total of 3 times. The first time, just watch and listen. The second time, watch and look for the date. The third time, watch for any details–what are they doing?

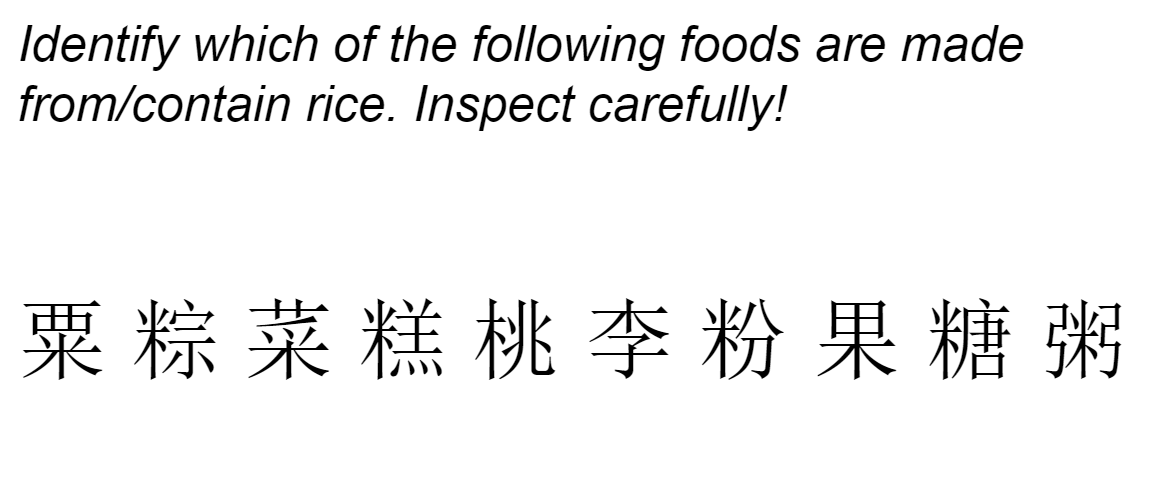

Mini-Lesson on negotiating meaning from unfamiliar Chinese characters.

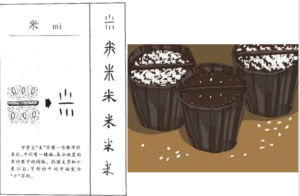

This is by far my favorite part of learning and teaching Chinese–Watching students learn to go from fearing blocks text riddled with unfamiliarity turn into puzzles just waiting to be solved. Here we looked at where the pictographic character “rice” came from (how it evolved as a pictograph into the current character we use). Many Chinese teachers fear that Chinese characters are “too much” for novices. I have found instead that they can be like a trail of candy for learners–give them just enough to keep them interested and moving forward–sorta like grains of rice?

[rule type=”basic”]

Task 3 (Interpretive Reading)

Task 3 (Interpretive Reading)

I told my students that I am vegan and gluten free and don’t eat any rice (which, in fact, could not be further from the truth, but we do what we have to for our students, right?). It was their job to keep my sensitive tummy safe from the many menacing grains–and they did it with the simplest language: The numbers 1-10 and 有 (it has),没有 (it does not have),上 (top) 下 (bottom) 左 (left) 右 (right). Can you find all of the rice?

The answers. I survived the “meal” with my students, would I have survived with you? Do you notice any more recurring components in those characters? Any possible patterns based on the pictures? (See how much you can know without even worrying about how to pronounce the character itself!?) Pieces of candy! [Hint: Look at all of the fruits]

[rule type=”basic”]

Task 4 (Interpretive Reading/Viewing & Presentational Writing)

Task 4 (Interpretive Reading/Viewing & Presentational Writing)

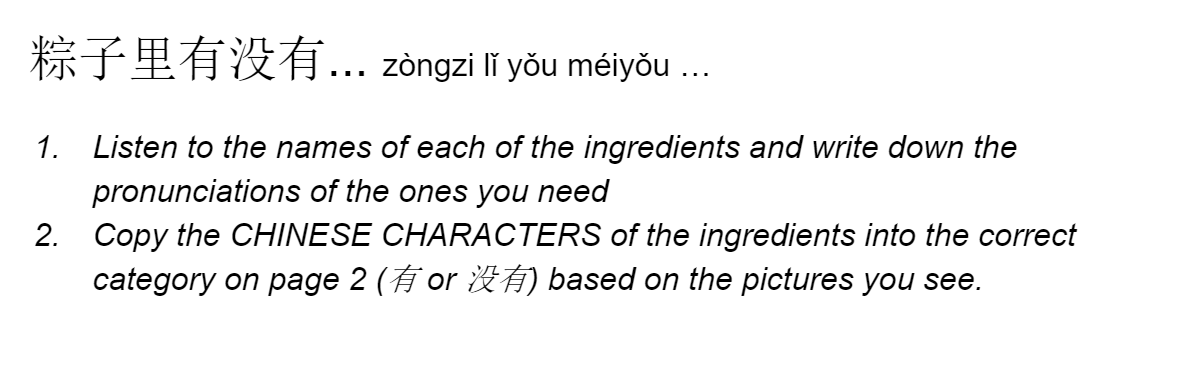

In this next task, we reviewed the list of ingredients they had in front of them (intentionally without Pinyin at all). Those they knew already, the did not need the Pinyin for. Those they needed, we figured out together (they had to listen carefully for the tone).

Students looked at 4 pictures of 粽子 (zongzi) and decided whether or not each ingredient was present. They then copied the Chinese characters (no pinyin) from the ingredients sheet into this table. Finally, they told me “yes” or “no” and had to tell me where they saw the ingredient in the pictures from my PPT (again using the numbers 1-4 and top, bottom, left & right).

[rule type=”basic”]

Task 5

Task 5

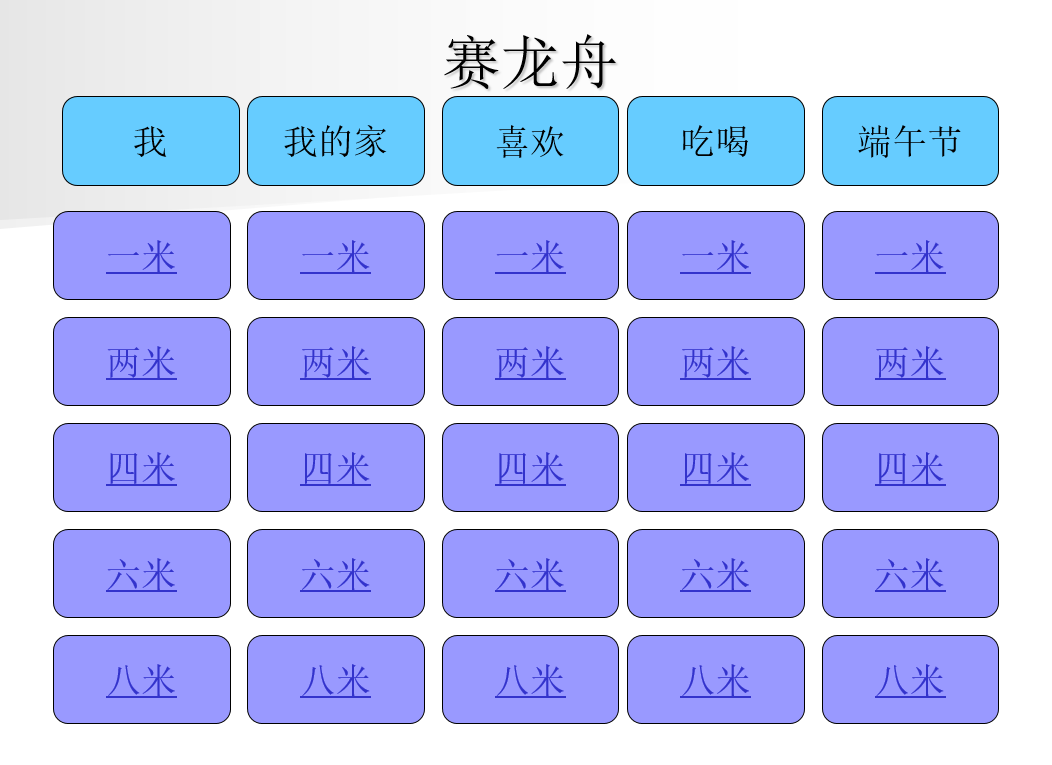

The Dragonboat Festival is, as you might have noticed in Task 2 above, comprised of 2 major practices & products–粽子 (sticky rice and other ingredients boiled or steamed in bamboo leaves) and 龙舟, Dragonboats (no kidding, right?). So, short of going to an actual lake and renting dragon boats to race, I decided to make a jeopardy game in which you get “meters” instead of dollars and move your boat along the river to save Quyuan (who is a drowning poet attempting to commit suicide after his country was conquered by future first emperor of China). Students competed in teams and had to answer every single question for points. The team that selected the question got 100% of the points if correct, and all other teams could get 50% of the points if correct. I learned this style of jeopardy from the wonderful Rosalyn Rhodes.

[rule type=”basic”]

My Reflections

What worked:

- Group formation – I gave each student a card with a color on the front and a number on the back. The color corresponded to a dragonboat on the board (their new boat) and I used the numbers to call on a particular student from each group to answer each question. This way, every single student had to be ready to answer every single question

- Limiting the prep time to 1 minute for everything but the hardest questions. For example, they were given 2 minutes to prepare to introduce everyone on their team and tell me 1 fact about each person besides their name.

- Encouraging my Novice Lows to perform at Novice High by offering them a 1 point bonus for answering my questions in complete sentences. I included scaffolded response starters in each slide that I could click to reveal if they were struggling (but trying) to use a complete sentence.

- Content – I pulled content from all of the topics they learned about over the three week program: Me (self introductions), My family (parents, siblings, etc.), Likes & Dislikes (mostly hobbies & the other culture activities they did), Eating & Drinking (Chinese food, what we saw on our field trip to a restaurant and market, etc.) and the Dragon Boat Festival (things we had just gone over in this lesson).

What didn’t work:

- I did not think to put an icon on each question to show students what was expected of them–were they supposed to write things down (if so, in pinyin or Chinese characters?) or just say them aloud? At first, I thought writing everything down made the most sense, since that way it would be fair no matter which order I asked for answers in. The student with the number I called from each team would should be his or her whiteboard, and I would award points. In the future, I will need to be more intentional in how I ask them to answer questions–all I needed was an icon in the corner!

- Not enough time! We (as I tend to do) got caught up learning and laughing in earlier tasks, so we were unfortunately only able to play this game for about 20 minutes. I adapted by doing a Final Jeopardy in which every team could get full points for the last round–these middle schoolers HAD to save Quyuan from drowning (and alter the course of history in the process!). In the future I would make these things two separate parts of 1 2-day lesson: Zongzi one day and then Dragonboats the following day.

My takeaways:

- Our students are much more capable than we think—we are limiting them in so many ways. I found myself constantly surprised that low novice learners were able to understand and do so much.

- Our students are not magical—they need guidance and scaffolding at all levels. They are, however, very smart and when you give them the patterns and the tools they need to mine for meaning, they will do it and blow your mind. This was especially true for me, I realized, when teaching students how to deal with unfamiliar Chinese characters (and avoid developing a reliance on pinyin–they only rely on that because we let them or make them!).

- Students need to be doing things—not just talking, not just reading about or watching videos about cultural products and practices, but actually “racing dragon boats” to “save Quyuan”. When they are having fun, they don’t even realize they are learning, and the enthusiasm when 70 minutes flies by and we review our I Can statements was truly incredible.

One student even told me “Gao Laoshi, we don’t really do any work in your class, I mean… it’s so easy! But I learn so much. You’re like, a wizard or something. Like the Chinese Dumbledore or something. By the way—can I have more tea?”

Hopefully, this has given you some insight into my classroom and some small nugget of an idea to take back to yours. Be on the lookout for part 2 and part 3, coming soon to theaters near you!

I do think it is essential for students to understand in depth the I can statement. By making students aware students can take ownership of their own learning. Also, I agree that it is important to chunk activities and allow students to practice all modes of communications,